Feature Article

The Changing Landscape of the Hardwood Lumber Industry

by Scott Bowe

The hardwood lumber industry has navigated significant changes over the past 25 years, marked by shifting global markets, domestic economic shocks, and a fundamental realignment of its primary consumers. From its peak production in the late 1990s to the complex, trade-dependent sector it is today, the industry’s evolution reflects broader trends in the American and global economies.

The Peak and the Pivot: A Departure from the 1990s

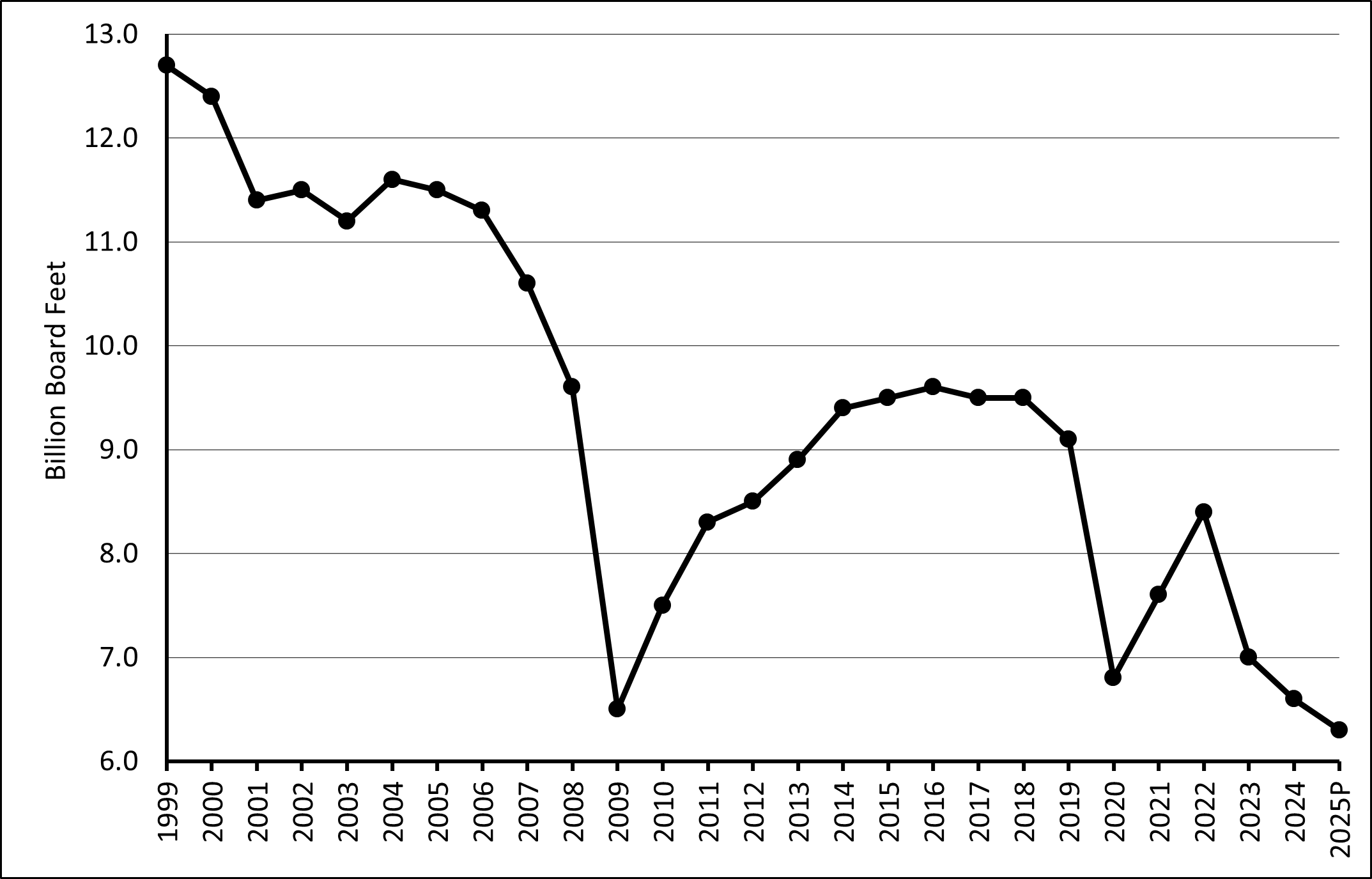

At the turn of the millennium, the U.S. hardwood industry was at a historic high. Eastern U.S. hardwood production reached its peak in 1999, with an estimated 12.6 billion board feet (Figure 1). During this era, the domestic furniture industry remained a dominant force, consuming a significant portion of high-grade lumber.

However, the early 2000s ushered in a major structural shift – the offshoring of U.S. furniture manufacturing. By 2002, the domestic furniture sector’s share of total U.S. hardwood lumber consumption had fallen to roughly 16%, down from a 1963 peak of 35%. As furniture factories moved overseas, the industry pivoted its focus toward the housing and construction markets, which were entering a period of robust growth. The Lake States were not isolated from these changes. Richardson Brothers was a well-known national name brand in hardwood dining furniture based in Sheboygan Falls, Wisconsin. After 150 years in business, they were forced to cease domestic manufacturing in the early 2000s, eventually becoming a brand name for imported goods before disappearing. Widdicomb Furniture Company, once a titan of furniture in Grand Rapids, Michigan, saw its final iterations fade away in the early 2000s as high-end domestic production costs became unsustainable. La-Z-Boy of Michigan, though known for upholstery, their wood "case goods" division (dining/bedroom) moved almost entirely to Asian sourcing (China and Vietnam) in the mid-2000s. However, Ashley Furniture maintains a massive presence in Arcadia, WI, they became the industry leader by becoming early adopters of a dual-sourcing model, building massive plants in China to supplement U.S. production.

Figure 1. Eastern U.S. hardwood lumber production estimates (Luppold and Bumgardner 2017; Bumgardner 2026).

The Housing Crisis: A Defining Downturn

The housing market crash of 2007–2008 remains the most significant disruption to the hardwood industry in recent history. The crisis profoundly reduced demand for "appearance-based" hardwood products, such as cabinetry, flooring, and millwork.

The impact was visible in every metric:

-

Production: Hardwood lumber production hit a deep low point in 2009 (Figure 1).

-

Employment: Employment in related sectors, such as wood kitchen cabinets and millwork, is highly correlated with single-family housing starts and saw dramatic declines during this period.

-

Industry Footprint: The number of hardwood sawmills and employees has steadily declined since 2005. By 2011, single-family housing starts reached a record low, just six years after their 2005 peak.

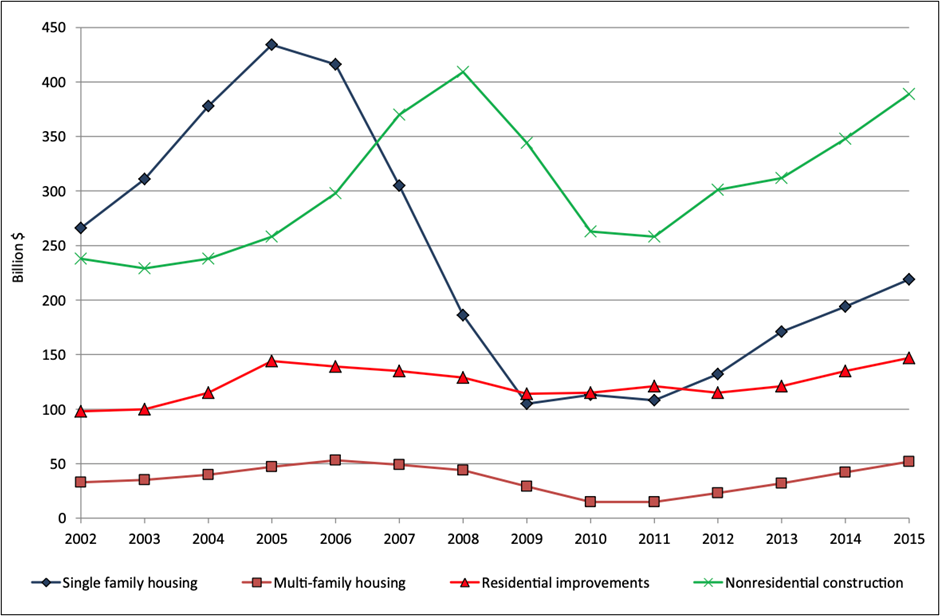

During the worst years of the crisis (2009–2011), the value of single-family construction even dropped below that of residential improvements & remodeling (Figure 2), as foreclosed homes required maintenance to become marketable.

Figure 2. Value of private US construction put in place, 2002 to 2024.

The Rise of the Export Market and the "China Factor"

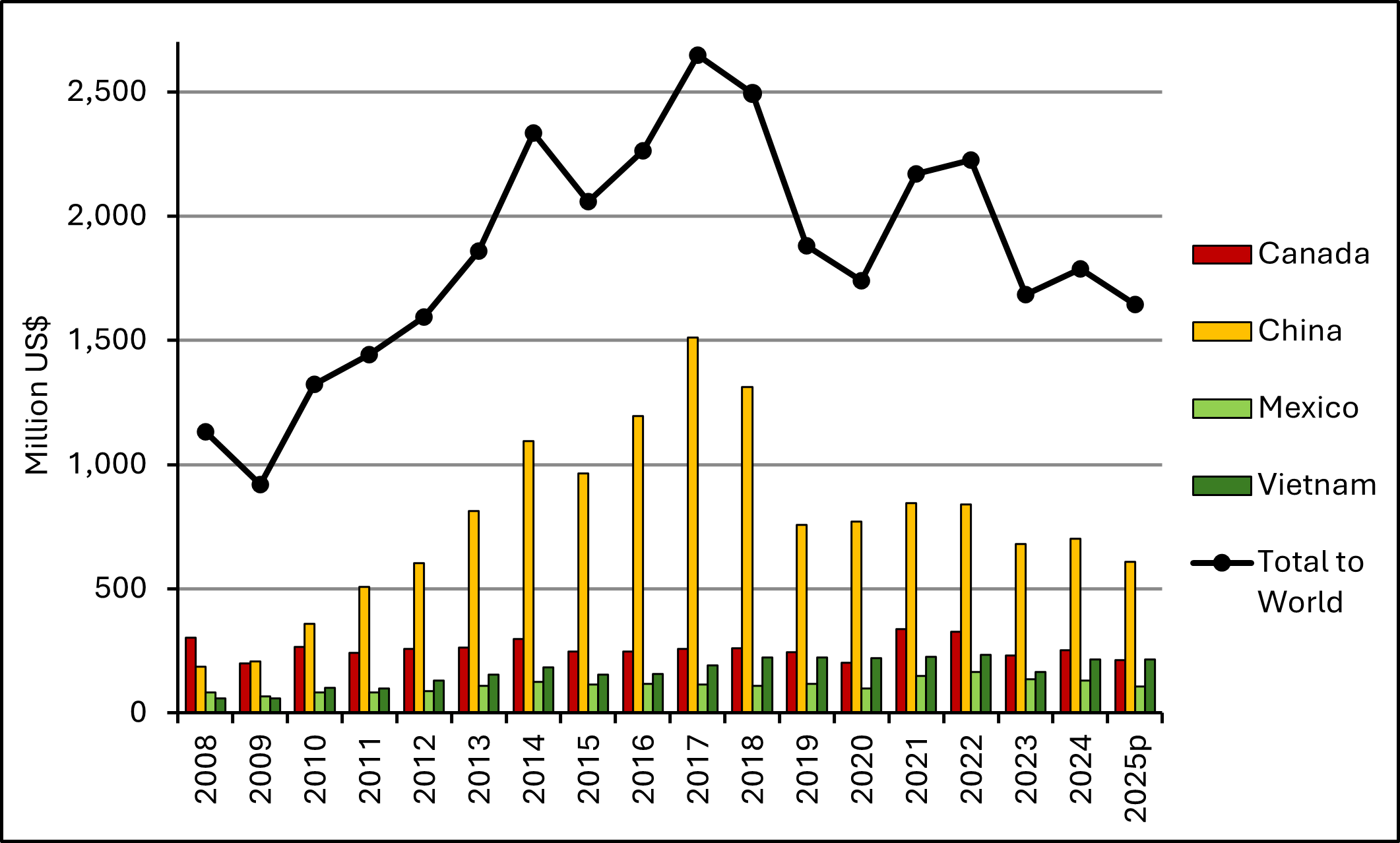

As domestic demand for high-grade lumber faltered during the housing crisis, exports became a lifeline for the industry. The percentage of total hardwood lumber consumption attributed to exports more than doubled from 8% in 1991 to 17% by 2014 (Figure 3).

China emerged as the single most important player in this new era. Its share of U.S. hardwood lumber exports surged from 16% in 2008 to 57% in 2017. By 2017, China was the largest export destination by a wide margin, accounting for $1.5 billion of the $2.6 billion in total hardwood exports (Figure 3). This shift created an unprecedented level of interconnectedness between U.S. sawmills and global economic events.

Figure 3. Top four destinations and world total for U.S. hardwood lumber exports (Data: USDA Foreign Agricultural Service).

Industrial Markets: The New Foundation

Another critical change over the last quarter-century has been the increased importance of industrial markets—such as pallets, packaging, barrels, and railway ties—for lower-value products. In the absence of strong furniture and housing markets, these "low-grade" sectors have become the largest domestic consumers of hardwood lumber.

By 2014, industrial products accounted for 51% of total hardwood lumber consumption, up from 39% in 2002. This shift underscores the industry's need to find consistent outlets for the entire log, not just the high-grade material used in appearance-based products.

Recent Challenges: COVID-19 and Trade Volatility

The last five years have introduced new layers of complexity. The industry faced another significant downturn in 2020 due to COVID-19 disruptions. While the market briefly recovered, 2023 brought a new decline driven by slowing global demand, a cooling housing market, and competition from substitute materials that continue to gain market share in several sectors. Substitute products, such as Luxury Vinyl Tile (LVT) and Luxury Vinyl Plank (LVP), have gained market share from solid and engineered hardwood flooring. LVT grew from representing roughly 28.7% of total flooring dollars in 2020 to over 34% by 2022. By 2024, LVT/LVP was projected to surpass carpet as the most popular flooring product in the US. The primary drivers were the COVID-19-era renovations, where consumers prioritized DIY-friendly, waterproof, and durable materials, particularly in kitchens and bathrooms. Technological advancements allowed LVT to closely mimic the appearance of hardwood at a lower price point. LVT also had some clever marketing working in its favor. Since when is plastic flooring a luxury!

Trade policy has also become a central concern. The 2018–2019 trade dispute with China had a lasting impact, and as of late 2025, the industry remains deeply focused on negotiations regarding tariffs and purchase requirements. Reports indicate that while framework deals have been agreed upon, commitments for hardwood lumber purchases have not always been met, leading to ongoing advocacy for federal trade assistance.

Looking Forward

The hardwood industry of today is leaner and more globalized than the one that entered the 21st century. While the number of establishments has fallen—the rate of decline accelerated during the housing crisis before leveling off around 2014—surviving companies have seen some stabilization.

Current trends suggest that while single-family housing remains the "gold standard" for demand, multi-family housing and remodeling will play increasingly important roles. Furthermore, the industry continues to explore innovations, such as cross-laminated timber, that could allow hardwoods to make inroads into nonresidential construction.

The last 25 years have proven that the hardwood industry is resilient, but its future depends on navigating a world where global trade, macroeconomic housing trends, and industrial efficiency are more tightly linked than ever before.

Scott Bowe is a Professor of Wood Products located at Kemp Natural Resources Station in Woodruff, Wisconsin.

Data for this article was based on research provided by Matthew Bumgardner, Research Forest Products Technologist with the USDA Forest Service.