From the President's Desk

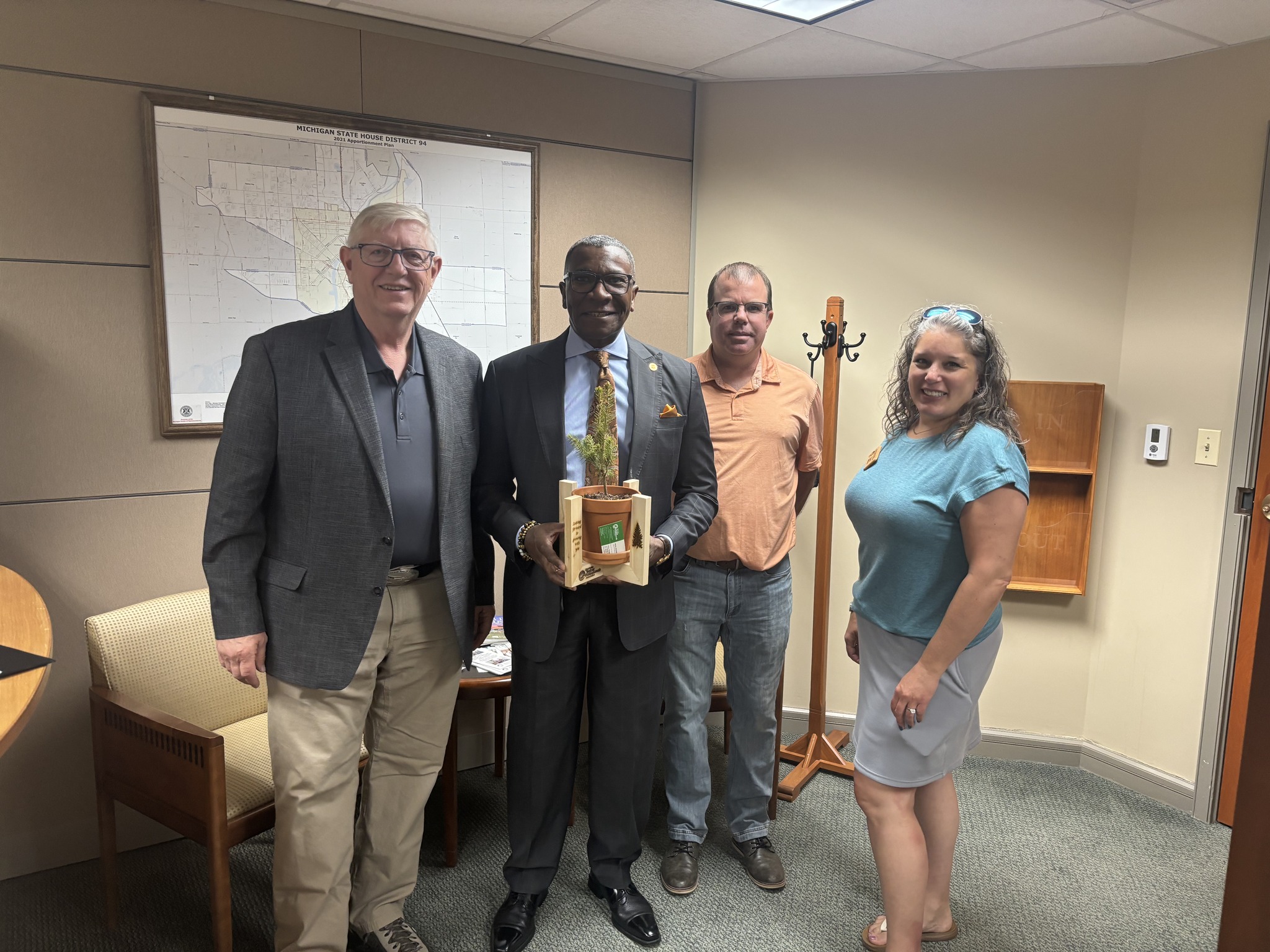

During the week of June 9th, GLTPA distributed Meyers spruce trees with attractive cedar stands to every member of the Michigan House and Senate. It was a joy to see their reactions of smiles and genuine excitement as we handed them each a tree. It turns out, almost everyone loves trees, and really, that makes perfect sense.

This experience reminded us how important it is for the logging and forest industries to improve their outreach. Too often, the public doesn’t see the full picture of what we do. Most Michiganders and Wisconsinites live far removed from the woods, where forest and forestry is not a daily reality but more of a once-a-year camping trip. It’s easy to forget that a healthy forest and a sustainable forestry industry are vital to our state’s well-being.

During our visits, many legislators and staffers were surprised that we didn’t come with an agenda. We were simply there to hand out trees and have conversations. Naturally, we discussed our work, and while some staffers kept it brief, others had a lot to share. As we moved through downstate offices, we found people genuinely surprised to see a tree growing in a pot with many admitting they had no idea how to care for one (It’s not too hard, just water and sunlight!)

One memorable visit was with Representative Amos O’Neal of Saginaw, who took time to talk in-depth with us. He was especially interested in how his office might support cleanup efforts from the recent storm damage in the Northern Lower Peninsula. That conversation and others stayed with me not just because the storm affected me but because I realized how many people no longer have a place to plant a tree. So many folks now live in apartments or condos. In contrast, those of us in forestry are lucky. We are surrounded by nature daily, not stuck in suburban traffic jams. Honestly, the biggest town I’ve ever driven my log truck through is Escanaba.

As we met with legislators and staff, we also invited them to the Capitol White House Fish Fry, a collaborative event hosted by GLTPA, Michigan’s Commercial Fishing Industry, ABATE of Michigan (American Bikers Aimed Toward Education), the Lake States Lumber Association, and others. At first glance, a group made up of loggers, bikers, and fishermen may seem like an odd mix, but we actually share a lot of common ground. For instance, ABATE and GLTPA both have concerns about road quality and funding. Whereas Michigan’s commercial fishing industry, like ours, must navigate regulations and work closely with the DNR.

Of course, the highlight of the Fish Fry was the food. The Commercial Fishing Industry cooked up freshly caught whitefish, lake trout, walleye, and perch. Thanks to Senator Ed McBroom’s suggestion, we also had ice cream, generously donated by Debacker Family Dairy out of Daggett in the western Upper Peninsula. I have not heard the official count of people attending but I am sure we served over 600 meals.

At the event, GLTPA and LSLA showcased the full cycle of sustainable forestry. We displayed young trees destined for planting at Michigan State University, alongside forestry equipment: a harvester, a forwarder, a loaded log truck, and a lumber truck with a shipment of railroad ties. Ironically the log truck was bound for the very same mill that produced the ties. It gave us a tremendous opportunity to talk with legislators and staffers about how our industry really works. For many, it was the first time they had ever seen this kind of equipment up close. One thing became clear, a surprising number of people still think we rely mostly on chainsaws. That just underscores how vital our educational outreach really is.

In the end, these visits and the Capitol Fish Fry were not just about handing out trees or serving up great food. It was about connections. This reminded us that people care when you take the time to show up, listen, and share your story. For the forestry and natural resource industries, these small moments of outreach can spark bigger conversations about sustainability and the role we all play in caring for Michigan’s and the regions land and water. I left inspired, and hopefully, so did those we met. Thank you to everyone who helped bring this event to life, especially Scot Evert and his team, whose hard work made it all possible.

In the end, these visits and the Capitol Fish Fry were not just about handing out trees or serving up great food. It was about connections. This reminded us that people care when you take the time to show up, listen, and share your story. For the forestry and natural resource industries, these small moments of outreach can spark bigger conversations about sustainability and the role we all play in caring for Michigan’s and the regions land and water. I left inspired, and hopefully, so did those we met. Thank you to everyone who helped bring this event to life, especially Scot Evert and his team, whose hard work made it all possible.

Mike Elenz

GLTPA President